Long Lead

Long Lead Presents

TheCatch

By Emily Sohn

Virginia Kraft was among the most important sports journalists of her time. A pioneering adventure writer who was deadly with a rifle, she chiseled early cracks into publishing’s male-dominated world. So why hasn’t anyone heard of her?

scrollTournament Day

“By mail and telephone we get many strange questions about sports and sportsmen. A man called here a few days ago wanting to know what kind of after-shave lotion the big-game hunters on our staff prefer. We were able to answer that one pretty easily. The only big-game hunter on our staff is Writer Virginia Kraft, and she doesn’t use the stuff. She does occasionally carry Chanel No. 5 on hunts...”

Letter from the PublisherSports IllustratedFebruary 22, 1965

A streak of fiery pink brightened the horizon, lighting up a line of clouds that towered like smokestacks over the bayou. It was 5:30 a.m. on a Monday in early June, and although the full moon had not yet set, the marina in the tiny outpost of Venice, Louisiana, was already awake. A pickup truck backed a boat to the edge of the water alongside a fleet of vessels lining an L-shaped dock. The smell of gas infused the salty air while captains filled tanks for a nine-hour day on the water. And from every direction arrived anglers — all of them women.

It was tournament day, the first of a three-day event hosted by the International Women’s Fishing Association (IWFA). Competitors, many of them longtime friends and all carrying fishing rods, greeted each other with exuberant hugs, cheek kisses, and selfies in front of the sunrise. They scanned the dock for the guides and partners they had been paired with for the day. Mary Weingart, a 65-year-old competitor from North Carolina, had risen at 4:30 a.m., eaten an egg-and-sausage biscuit with grits, and gulped a cup of coffee. Now she was out by the dock, where she couldn’t find her guide, Jack. The night before they had agreed on a 5:30 meetup. “If you tell me to be here at 5:30,” she grumbled, “I’m here at 5:30.”

Leiza Fitzgerald, of Sarasota, Florida, left, and Connie O’Day, right, of Pearland, Texas, head to their boats before the 2023 Louisiana SLAM Tournament begins on June 5, 2023. Kathleen Flynn/Long Lead

An all-women’s fishing tournament is nothing new in 2023, but the concept was revolutionary back in 1955, when a group of women decided to leave their husbands at home and start the IWFA — a history I knew about because of Virginia Kraft. In 1960, Kraft first wrote about the IWFA for Sports Illustrated (SI), making her — at the time and for a long time after — one of the only women writing the kinds of in-depth stories the magazine became known for.

Over a 26-year career at SI, Kraft wrote deeply reported and immersive features, just like her male colleagues. All the while, she quietly racked up an unrivaled collection of firsts. She was the first woman to race in a major dogsled event in Alaska, the first woman and first foreign journalist to hunt with General Francisco Franco of Spain, and likely the only mother of four to traverse six continents to take down all of the Big Five trophy animals. Yet despite the enduring reputation enjoyed by her male contemporaries at SI — including George Plimpton, Frank Deford, and Roy Blount Jr. — her work has since faded into obscurity.

Despite more than 100 SI bylines and significant accolades and attention in her time, Kraft is absent from lists of pioneering women in journalism, and her articles are excluded from discussions of notable SI stories. Her work isn’t covered in journalism schools, and when asked, none of my peers was even familiar with her name. Virginia Kraft might be the most influential sports journalist nobody has ever heard of. Why?

The more I learned about her, the more compelled I was to answer this question. My start in adventure-based journalism came in 2001, more than 50 years after Kraft’s, when I joined a mostly male expedition team to write about animals and the environment in the Peruvian Amazon, Turkey, Cuba, and other remote places where I was always outnumbered by men and sometimes the only woman. Since then, I have hiked up mountains, trekked through jungles, and even skateboarded down ramps for my work — never considering whether I could or should do it, even when I left my children behind. In fact, more often I was motivated to demonstrate, through my work, that women can achieve whatever they want.

When I first heard about Virginia Kraft, she seemed to be a classic overlooked hero, a woman who had chiseled early cracks into a male-dominated world that would eventually open enough to make way for my own writing career. Delving into her life and writing in the context of 1950s New York, however, revealed a complicated story of a woman who did not fit into simple boxes, and whose career challenged my expectations of what it means to be a pioneer.

To figure out why she had been forgotten, I scoured Kraft’s words for clues about what it was like to be one of the first. This research led me to the women of the modern-day IWFA. In 1960, Kraft covered the group’s fifth annual sailfish tournament. It was “perhaps the most unusual fishing contest in America,” she wrote, drawing competitors from around the continent “to show the male world, which has long excluded women from fishing competition, that the International Women’s Fishing Association was ready to compete with anyone.”

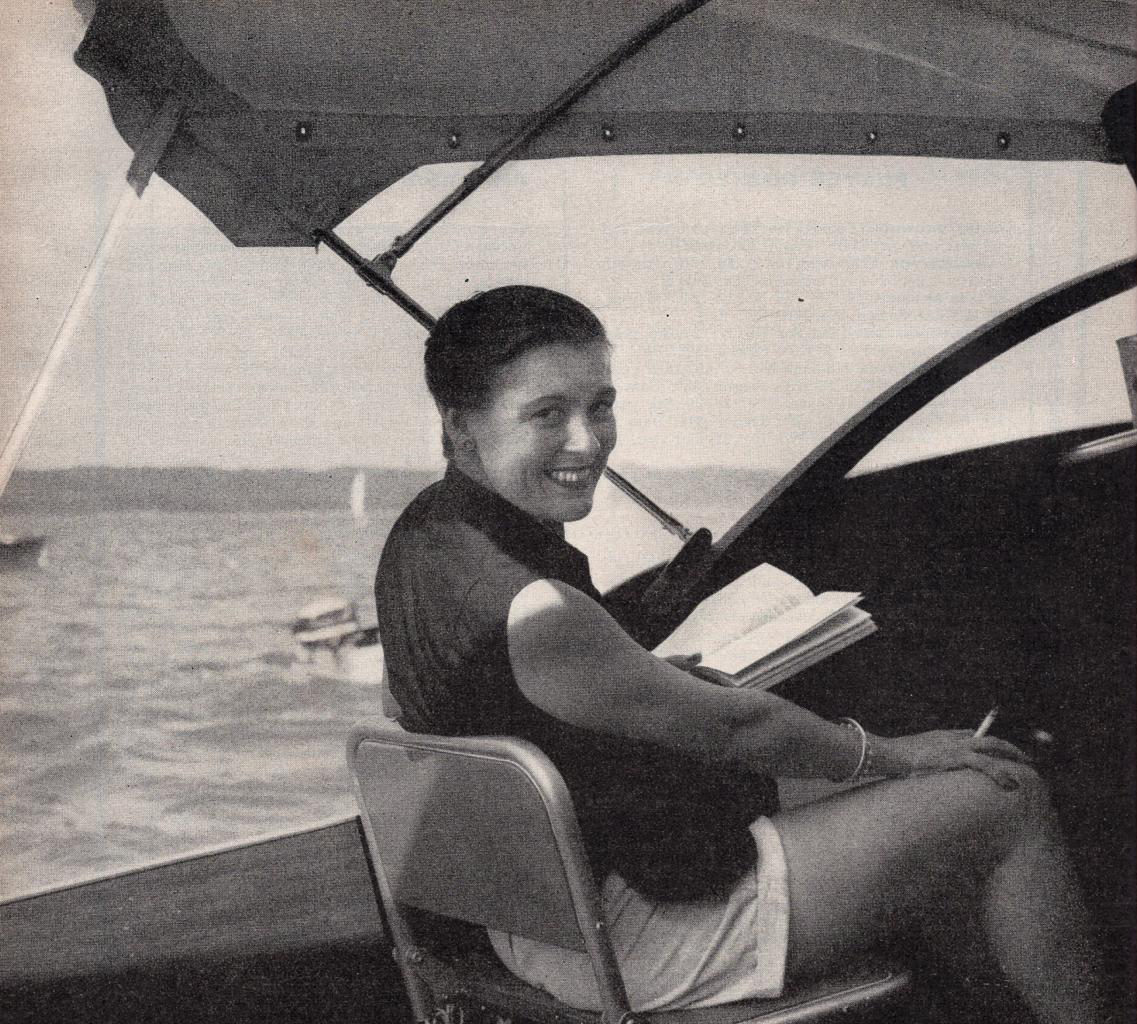

Virginia Kraft enjoys a cigarette and a mystery novel while boating down Kentucky Lake in the Tennessee Valley, 1958. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland

Eager to see how that description held up 63 years later, I contacted IWFA President Denise Freihofer and asked to watch the group’s upcoming tournament. She tried to talk me out of it. It would be hot, she said, adding that everyone would be too busy fishing to talk to me during the day, and afterward they might be too tired. And, she piled on, boat captains are secretive about their fishing spots and would likely not want me following them.

“We would hate to think of you traveling with your guide and not be able to find any of us,” she wrote in an email. “How disappointing that would be for you.”

. . . a complicated story of a woman who did not fit into simple boxes, and whose career challenged my expectations of what it means to be a pioneer.

Virginia Kraft would have been undeterred by Freihofer’s discouraging words. Stories of her confidence were legendary among those who remember her best. During a trip to Cuba in 1956, she knocked on Ernest Hemingway’s front door without any notice. He answered wearing yellow pajamas. She told him her name, which he recognized from her work, and he invited her in. They spent the morning drinking together. “I mean, who does that?” recalled family friend Christian Erickson, who is also the trustee of her estate. “She was not afraid to take risks, and she did. Nine times out of 10, it worked out.”

Channeling Kraft — or, at least, who I thought she was — I replied to Freihofer that I was willing to get hot and I’d take my chances with getting ditched.

“OK,” she wrote back. “I can see you are going to Venice!”

THE SHREWD DEAL

“Although it surprises some people, we do not consider it unusual that our big-game expert is a lady who has taken trophies on five continents and has fallen down the sides of a few mountains in the process. There are something like 18 million licensed hunters in this country. The Winchester gun manufacturers estimate that about one million of these are women. Winchester admits that this estimate is little better than a wild guess, but it seems reasonable to us because wherever hunting guns are fired today, in local bogs or on distant scarps, we find a growing proportion of women.”

Letter from the PublisherSports IllustratedFebruary 22, 1965

Virginia Kraft was born in Astoria, New York — a neighborhood in Queens, across the East River from the Upper East Side of Manhattan — on February 19, 1930. Her Canadian mother Mary Flora Gillis, known to most as Jean, was the daughter of a prominent Nova Scotian builder who also ran a bottling plant. Jean was a housewife who had dinner on the table every night at 6 p.m. Kraft’s father George John Kraft, born to working-class German immigrants, became a successful sales executive, first for a printing company and later for Johnson & Johnson.

As a kid, Kraft loved spending time outside during the day and listening to the radio at night. She owned her first horse at age 8 and played polo as a young child. She and her younger sister Jacqueline spent summers with their family on Long Island. After excelling in high school, she went on to attend Barnard, an all-women’s college in Manhattan, where she majored in English and participated in extracurriculars like the student newspaper, the junior class play, the Newman Club, and other social committees.

Kraft was also the subject of a 1949 college newspaper story about a coed European tour she was organizing at Eastern colleges to take place the following year. For $1,148 — the equivalent of nearly $15,000 today — students on the all-inclusive trip would visit England, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and France. “This is a tour I have arranged for myself and students like myself,” she told the paper, “who would otherwise go to Europe alone, with no experience arranging accommodations and travel.”

After graduating in 1951, Kraft wanted to work in magazines but wasn’t content with the typical roles open to women as secretaries or on staff at women’s publications. She had been raised to do something different. When she was just 5 or 6 years old, Kraft recounted in a speech to Siena College graduates in 2012, her father lifted her onto a windowsill on a clear night and pointed to the full moon, which looked close enough to touch. “You can go there someday,” he told her, decades before space travel was a reality. “You can do anything you want as long as you want it and work for it. The whole universe is out there waiting for you.”

What she wanted was excitement and something other than writing about hemlines. So she opened the phone book and started searching for outdoor publications. The first listing she saw was Field & Stream, the preeminent outdoor magazine at the time. She had no real experience relevant to the hunting and fishing publication, but she walked into the office cold and talked to an editor who was “at first somewhat startled at the prospect of a young woman invading his bastion of maledom,” Kraft told Siena graduates. He quickly calculated that he could pay her a third of what men earned for the same job, but she would still make three times what she could at fashion magazines. “We both felt we had made a pretty shrewd deal.”

He quickly calculated that he could pay her a third of what men earned for the same job, but she would still make three times what she could at fashion magazines.

Over the years, articles written about Kraft provided various accounts on how and when she learned to hunt. Among them: she started as a child, she taught herself to shoot in order to land her first job, she learned from her first husband, and she learned while at SI. In her speech to Siena graduates, she said she learned to fish and hunt — first with a bow and arrow, then with a gun — on weekends while at Field & Stream. However it started, she was seemingly willing to fake it until she made it. “She kind of bullshitted her way into the job,” says Erickson, citing the version he was told. “She’d never hunted in her life.”

Kraft soon got her first introduction to what it was going to take to succeed in a heavily male space. Forgoing recognition was part of the deal. While there, she wrote for the magazine under a male pseudonym: Seth Briggs.

As Briggs, Kraft appears to have been responsible for writing a one-page running feature called “Outdoor Questions.” Briggs — or Kraft — addressed reader questions, mostly about animals, hunting, and camping: how to keep butter fresh on a camping trip, why whales die when they’re beached, how long venison can last in a freezer before it spoils, if a black bear can run at 50 miles per hour, and whether a lion or tiger was the superior beast.

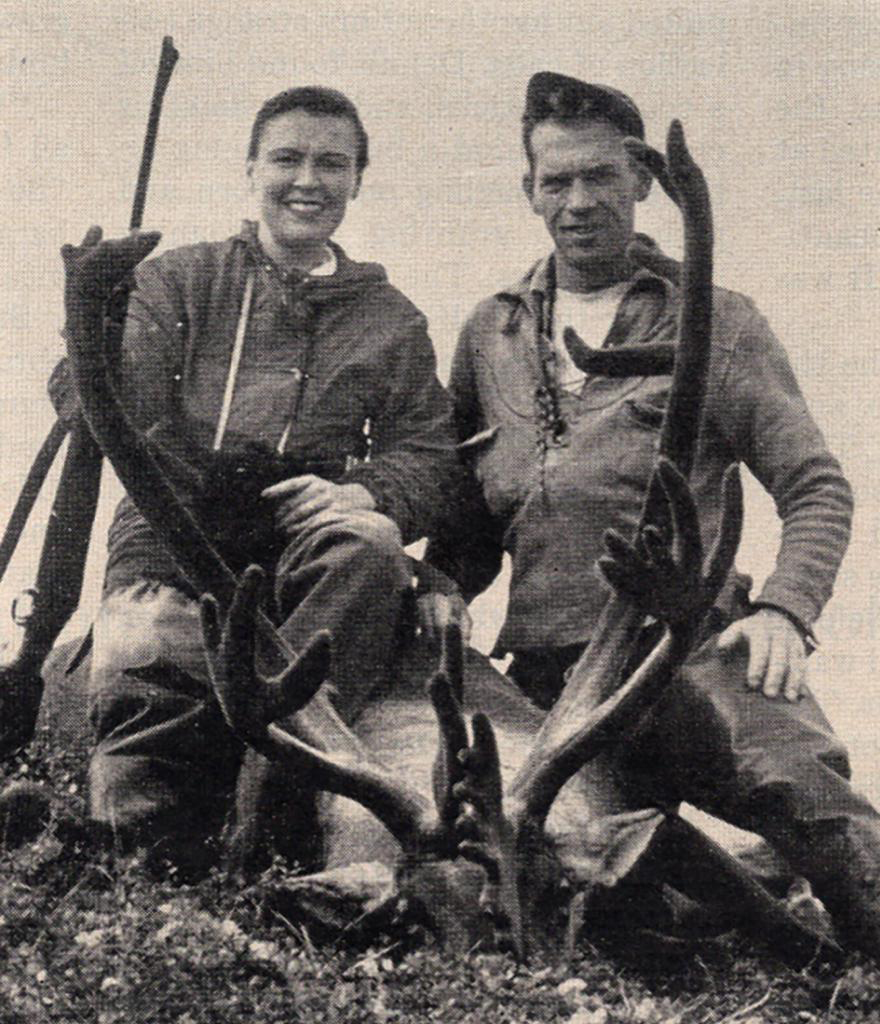

Virginia Kraft and her guide, Dennis Branham, pose with her first kill of an Alaskan safari, a Barren Ground caribou, 1959. Courtesy Virginia Kraft Payson Estate

Although Kraft’s name never appeared in the magazine, reading the column with her in mind conjures an image of a young, ambitious writer, collecting knowledge, accumulating experience, and patiently observing men in the workplace. Briggs’ answers, assuming they were written by Kraft, reveal occasional hints of an emerging voice and a hardening point of view. In July 1953, an amateur fisherman told “Outdoor Questions” about the guilt he felt every time he hooked a fish. “Actually, I don’t think there is much pain at all,” answered Briggs/Kraft. “The low state of development of the nervous system apparently explains why a fish is relatively insensible to the pain caused by a hook.”

Briggs, not Kraft, appeared on the masthead as an associate editor when she started at Field & Stream, becoming “department editor” at the end of 1953. But the name actually preceded her, first appearing in the magazine starting in 1927 and remaining there for years after Kraft moved to SI. It suggests “Briggs” was a placeholder name for staffers who hadn’t yet made a name for themselves — a regular practice in many magazines and newspapers at the time.

At Field & Stream, Kraft worked hard. Whereas the rest of the staff left at 5 p.m., even if they were mid-sentence, she stayed at least until 7, sometimes later, studying the archives from A to Z. Over a year and a half, she “gained a Masters-worth of knowledge about the outdoors,” she said, and she used that knowledge to hone her outdoor skills. Still, there didn’t seem to be much in the way of additional writing opportunities for Kraft at Field & Stream. Although a female byline occasionally appeared on the publication’s pages in the early 1950s, those stories tended to follow entrenched gender stereotypes, like a complaint-filled essay entitled “I Married a Fisherman.”

How Kraft felt about her work appearing under a male name remains a matter of speculation. It’s possible she was unbothered, happy to get valuable experience. But if she was like every other writer I know, she wanted to write under her own name. As she bided her time and practiced writing convincingly as a man, she could have studied her male colleagues and their confidence. It didn’t take long for her to get her shot.

A CLEAR HIERARCHY

“For the first time since I had stepped from the cab at the palace gates, the guards, soldiers and servants mysteriously vanished, and I found myself entering the imperial reception room alone. Before I realized what had happened, a gray haired man in a double-breasted suit was striding toward me with the long, smooth steps of an athlete, his hand outstretched and a broad smile on his surprisingly young face, fixing his warm brown eyes directly on mine, the Shah of Iran said in a soft, low voice, ‘I have been waiting a long time for your visit.’”

Virginia Kraft

“A Lady Hunts With the Shah”Sports IllustratedDecember 24, 1962

The early ‘50s, when Kraft started in journalism, was the Mad Men era, and according to Michael MacCambridge, author of the The Franchise: A History of Sports Illustrated Magazine, Time Inc. was “Mad Men on steroids.” The company, based in midtown Manhattan, already published Time, Life, and Fortune magazines. Looking to add to their portfolio, discussions began about relaunching SI, reviving the title of two previously failed publications by other publishers.

Conversations about the third iteration of the magazine involved booze, crude conversations, and jokes about whorehouses. To hash out the details, 67 male executives from Time Inc. met at a country club in South Carolina in 1954. There was golf. But, likely, no women.

Kraft left Field & Stream and joined the new SI staff as a reporter. Like most of the other women hires, she would have a supporting role for the heavily male writing and editing staff. But she didn’t see why her gender should get in the way of her ambitions. “The magazine was brand new, the beats were up for grabs, and advancement was based on performance and competition — being male or female had nothing to do with it,” she told a reporter for Copley News Service in 1975. “So I ended up on what is considered the most ‘masculine’ beat — hunting.”

The first issue of the relaunched SI hit newsstands on August 16, 1954. From cover to cover, more than half of its 148 pages were advertisements, heralding Ford Thunderbirds, Chryslers, Goodyear tires, Seagram’s gin, a new automatic shotgun produced by Winchester, and Skyway luggage “geared to the needs of a man who gets around.” Only a handful depicted women or women’s goods: the department store Bonwit Teller, Keepsake engagement rings, Vassarette shapewear, and Samsonite suitcases.

A news vendor looks through the premiere issue of Sports Illustrated magazine in his stand, New York, New York, August 16, 1954. Susan Wood/Getty Images

Every story was written by a man and all were about men, animals, or both. Features covered Roger Bannister, who had recently run the first sub-4-minute mile; a court battle between bubble gum manufacturers over baseball trading cards; and an appreciation of the important role that beavers play in protecting forests. Although no stories were about women, they appeared in photographs, including a “pretty, well-tanned” 15-year-old golfer, Betsy Cullen, who would later become a professional.

A woman did show up, sort of, in a cheeky one-page feature department called “Hotbox,” which asked readers to respond to the question, “What sport provokes the most arguments in your home?” Golf was the response given by Warren Austin Jr., an attorney from Burlington, Vermont, whose wife remained nameless and faceless in his answer even as he praised her skills. “My wife was afraid of becoming a golf widow,” he wrote. “I didn’t want her to tag along, but she would trail me to the country club against my orders. There she’d take golf lessons. Now she teaches me. It’s downright humiliating. But the arguments are not so frequent. She’s won.”

The women, including Kraft, who helped make that first issue happen worked behind the scenes as assistants and reporters. From the get-go, they conducted interviews, got quotes, checked facts, and did all the grunt work for writers. The job was a place to prove your worth. If you were good, you might work your way up to a writer position, says Curry Kirkpatrick, who joined SI as a reporter in 1966 and transitioned to writing during his 27 years there.

The women, including Kraft. . . worked behind the scenes as assistants and reporters.

There was a clear hierarchy. After Time Inc. relocated its offices within midtown Manhattan to the 20th floor of a 48-story skyscraper in 1959, reporters toiled away in cubicles in a large room called the bullpen, whereas writers and editors worked at the other end of the hallway. By the time Kirkpatrick arrived, Kraft’s door was down that hall.

Although Kraft has been described as the first woman on staff at SI, she wasn’t the only woman reporter on the masthead in the early months, nor was she the first to become a staff writer. But she was the only one who soon moved into a steady writing job that involved major adventure.

In 1954, Kraft joined a pheasant hunt with other members of the SI staff at a preserve in upstate New York. Also on the trip was Red Smith, a New York Herald Tribune columnist and frequent SI contributor whose later work for The New York Times was syndicated in nearly 300 papers nationwide and earned him a Pulitzer. Smith noticed Kraft, who showed up the night before the other staffers, went out early the next morning, and shot a buck with a brand-new shotgun. Smith’s column about the hunt, which appeared in December that year, described Kraft as a “pretty gun moll” who “smiled with cool composure” but confessed that the sport was new to her. “It was the first deer I ever saw,” said Kraft, who told Siena graduates that the hunt is how she landed the SI job. A few months later she wrote her first story.

On May 2, 1955, less than a year after starting with the magazine, Kraft’s debut bylined article appeared, an ambitious feature about joining General Francisco Franco’s hunting party. The over-the-top expedition was a massacre: 92 hunters and 350 servants downed 34 boars and 82 bucks, including a 20-point stag. Even though Kraft never fired a shot, raising her gun only once, it was a dramatic opener. The story set the template for her career at SI.

Kraft and other hunters walk through the dawn light of Terhel Farms near Colusa, California, 1966. Richard Meek/Sports Illustrated

How Kraft managed to land this first assignment is uncertain — it was likely part of a press junket organized in partnership with other Time Inc. publications, says MacCambridge — but she would go on to write dozens of similar stories about hunting and fishing in exotic locales, often with notable, wealthy, and sometimes controversial men. There is no sign that she or SI were bothered by Franco’s fascist and dictatorial regime — or by the carnage of the hunt.

Not long after starting at SI, Kraft met her first husband, Robert Grimm, at a cocktail party in New York City, says her oldest daughter Tana Aurland. Wealthy and 10 years older than Kraft, Grimm had done his share of traveling before they met, once spending two months in Cannes, France. He eventually owned an advertising agency and marketed his own inventions, including a cigarette holder. After they married in 1955, Kraft moved in with him at the Gipsy Trail Club, a private membership community in Carmel, New York. “It’s 60 miles to midtown Manhattan but may as well be 600,” Kraft told a newspaper reporter. The enclave, still active today, includes a clubhouse, a horse stable, tennis courts, and space for trap shooting. With easy access to hunting near home, Kraft honed her stalking skills, cultivating both an obsession and a path toward career advancement and notoriety.

STONE-COLD KILLER

“Marion Rice Hart, the pilot, is indeed a little old lady, though at 83 the description makes her cringe almost as much as when she is called ‘Widow Hart’ or a ‘flying grandmother’. She is quick to point out that she is neither. While she has no objections to motherhood other than that it leads to grandmotherhood, she has never been a mother, and she was divorced, not widowed, from a fellow named Hart whom she did object to because he insisted on asking her why she could not act like other women.”

Virginia Kraft

“Flying in the Face of Age”Sports IllustratedJanuary 13, 1975

Sports Illustrated was already covering hunting and fishing sporadically, but Kraft soon staked claim to the beat. Before long she was regularly striking out on harrowing adventures in wild places. In November 1957, for example, she wrote of her travels to the Bob Marshall Wilderness, a vast roadless area in Montana. Taking along a single pair of pants, six pairs of socks, camping gear, a variety of warm layers, and perfume in lieu of deodorant, she set out on horseback at around 5 a.m. with three guides — two state game rangers and a game biologist, all male — in pursuit of elk and skittish mountain goats.

After six miles on horseback, the quartet started to hike, scrambling on hands and feet over shale slides. Navigating wide crevasses, they climbed to the top of a 9,000-foot mountain, where they spotted five mountain goats on the other side of a boulder-strewn canyon. Then came nearly an hour of tiptoeing, crawling, and zigzagging to stay downwind. Once Kraft had crept close enough, she aimed and shot, bringing down the biggest of the five.

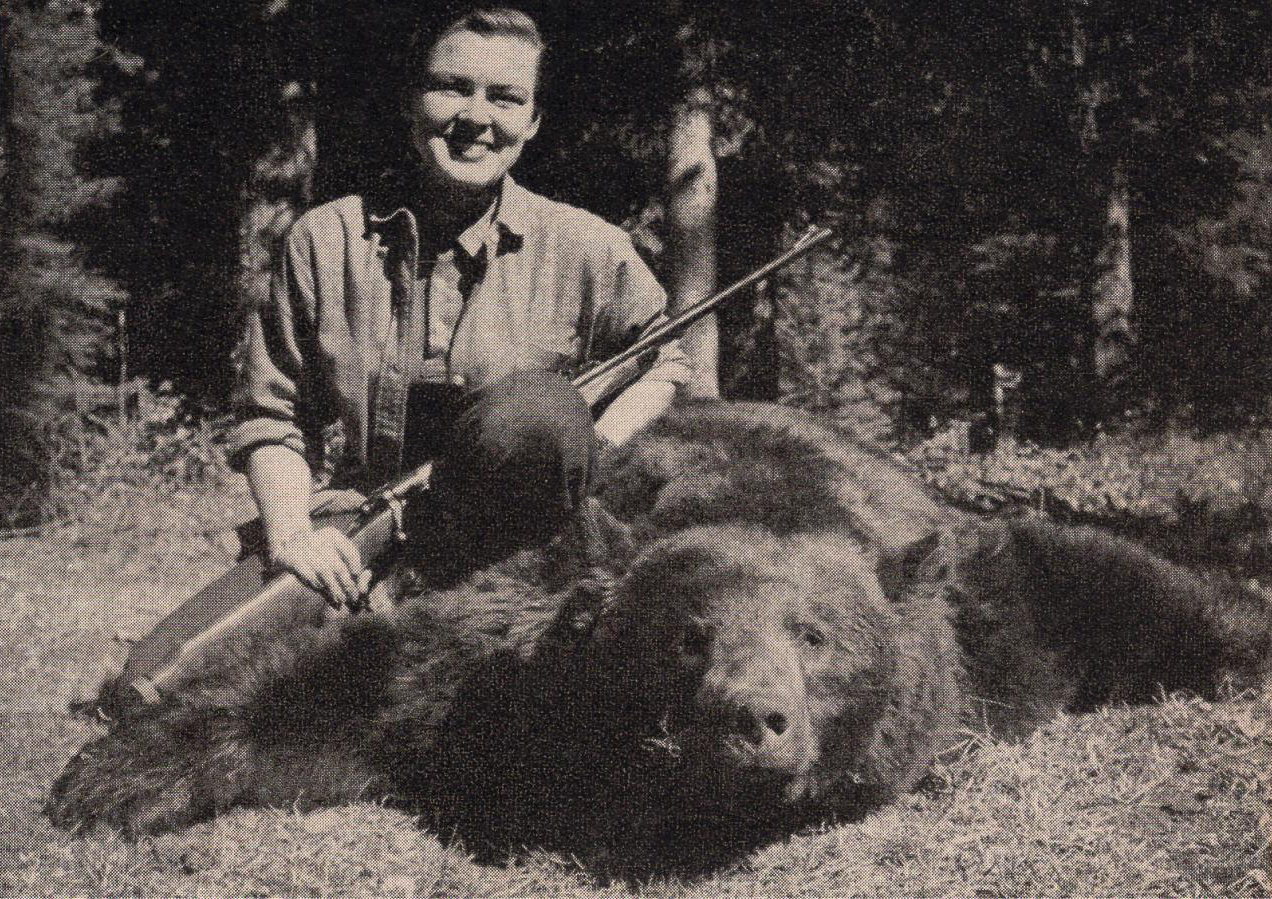

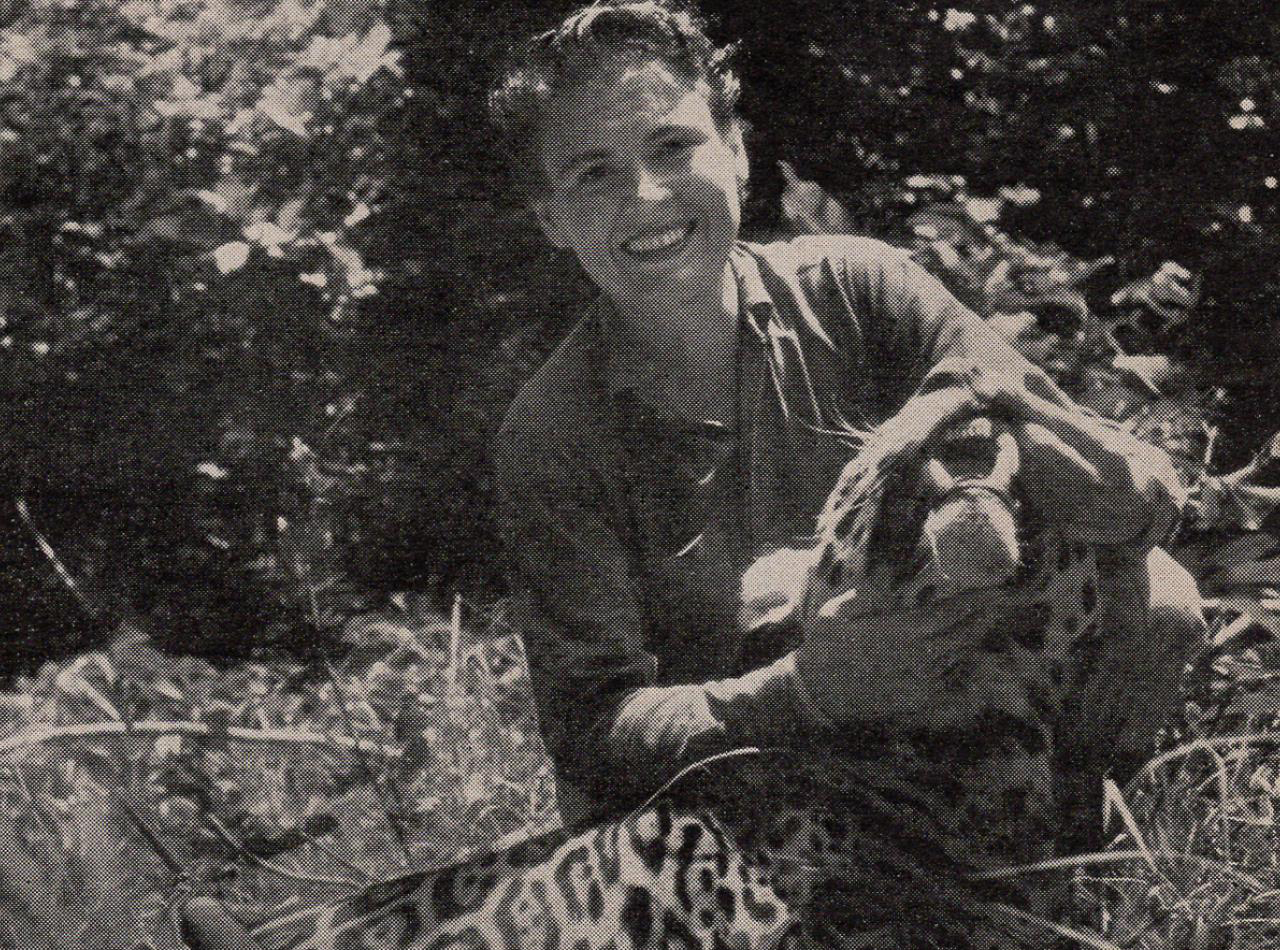

The story’s multipage spread features a photo of Kraft, then 27, crouching behind her trophy goat, holding up its horned head, smiling as though there were nowhere else she would rather be. In a larger photo, she holds a rifle and beams over another trophy: a 400-pound black bear that wandered into camp. “It was quickly converted,” she wrote, “into a long-desired bearskin rug.”

Virginia Kraft beams next to a trophy bear, on assignment for Sports Illustrated in Montana, 1957. Photo by Ross Wilson

Stories written about Kraft in the 1950s and ‘60s often dwelled on her looks and femininity. She was a “brunette beauty with sparkling eyes” that shone with the ruddy glow that comes from time spent outdoors. On her travels, she styled her hair, packed a full set of perfumes and face creams, and wore bespoke hunting pants, boots, and gloves with leather backs and corduroy fingers. As fit as Kraft was — 5’4" and maybe 120 lbs. — she didn’t look it. One female reporter noted, “Despite the fact that Virginia’s athletic abilities are such that she could outclimb the Shah’s own Master of the Hunt in the rugged 20,000-foot Iranian mountains, Virginia Kraft gives no hint of muscles in her looks or delightful manner.”

Writers who covered her accomplishments also marveled at how such a beautiful woman could hunt so well. “When pretty Virginia Kraft talks about outdoor sports, the men perk up their ears and listen, and when she writes, the men read every word,” reads a 1959 United Press International article about a lecture Kraft gave to an all-male audience. “The reason — simply that Virginia Kraft, or Mrs. Robert Grimm in private life — really speaks man language on the subject of hunting or fishing.”

“When pretty Virginia Kraft talks about outdoor sports, the men perk up their ears and listen, and when she writes, the men read every word.”

— United Press International, 1959For her part, Kraft argued that women’s patience made them particularly good hunters. She may have spoken with the accent of a New Yorker and looked enough like an all-American model to once appear in an ad for Family Circle magazine, but in the wilderness of men, she moved with stealth.

Kraft came up with many of her own story ideas, Aurland says, and they often involved exotic places and notable people. Apart from Franco, she hunted with the Shah of Iran, the king and queen of Nepal, and King Hussein of Jordan. Grimm accompanied her on some expeditions, doubling as photographer and companion in places where it was considered culturally inappropriate for a woman to travel alone. Accommodations could be lavish. To prepare for the hunt in Nepal, 1,100 locals spent two months clearing trails and landing strips in the jungle. The hunting party included at least two dozen jeeps.

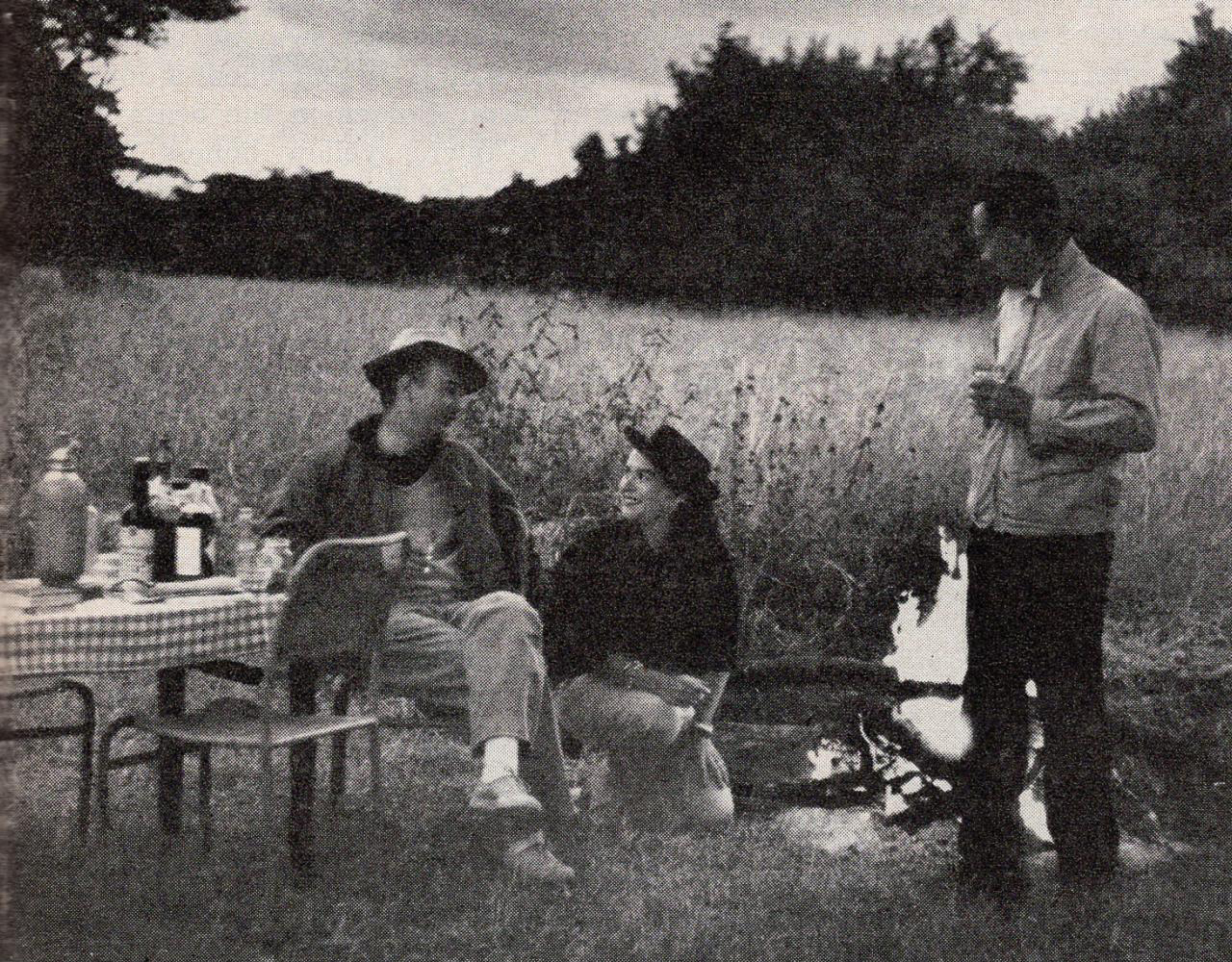

Robert Grimm, Virginia Kraft, and their guide Owen, enjoy a campfire and martinis after a day of hunting on an African safari, 1957. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland

Diving into Kraft’s life and work, I found a lot to admire. But her decision to go all-in on hunting as a beat planted seeds of discomfort in me. My writing about animals, conservation, and the environment in the 21st century tends to focus on saving species, not killing them. I haven’t eaten meat since I was 19. But Kraft — whom Erickson affectionately described as a “stone-cold killer” — slaughtered just about every major charismatic creature on earth, detailing the drama of her hunts in the pages of a major national magazine. Then, after filing her stories, she kept and displayed their heads, tusks, and bodies as trophies. How could I look to her as a hero when so many of the stories she told made me wince in pain?

IN HER SIGHTS

“At first I did not see it, so perfectly did it blend into the blacks and grays and golds of the jungle’s filtered sunlight. It watched me with fierce, amber eyes, as if it had known of this meeting all along and had been waiting for me to arrive. This was the big cat, the king of the New World, the prize at the end of a search that had begun almost 10 years before. Ten years of plotting and planning, and more than 10,000 miles of traveling, had led me finally to the base of this tree in the Mato Grosso (Great Forest) of Brazil, deep in the interior of South America.”

Virginia Kraft

“A Meeting in the Mato Grosso”Sports IllustratedFebruary 22, 1965

In 2011, while in the jungle of Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula, I interviewed a jaguar researcher, a woman who had been studying the elusive and increasingly rare animals for eight years but had never seen one in the wild. I thought of that biologist again when I read about Kraft’s own encounter with a jaguar.

She had already taken several fruitless trips in search of the wild cats in Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela. In October 1964, she made another attempt, this time to the Brazilian Mato Grosso, a vast, hard-to-get-to tropical forest full of swamps created by thousands of tributaries of the Paraguay River.

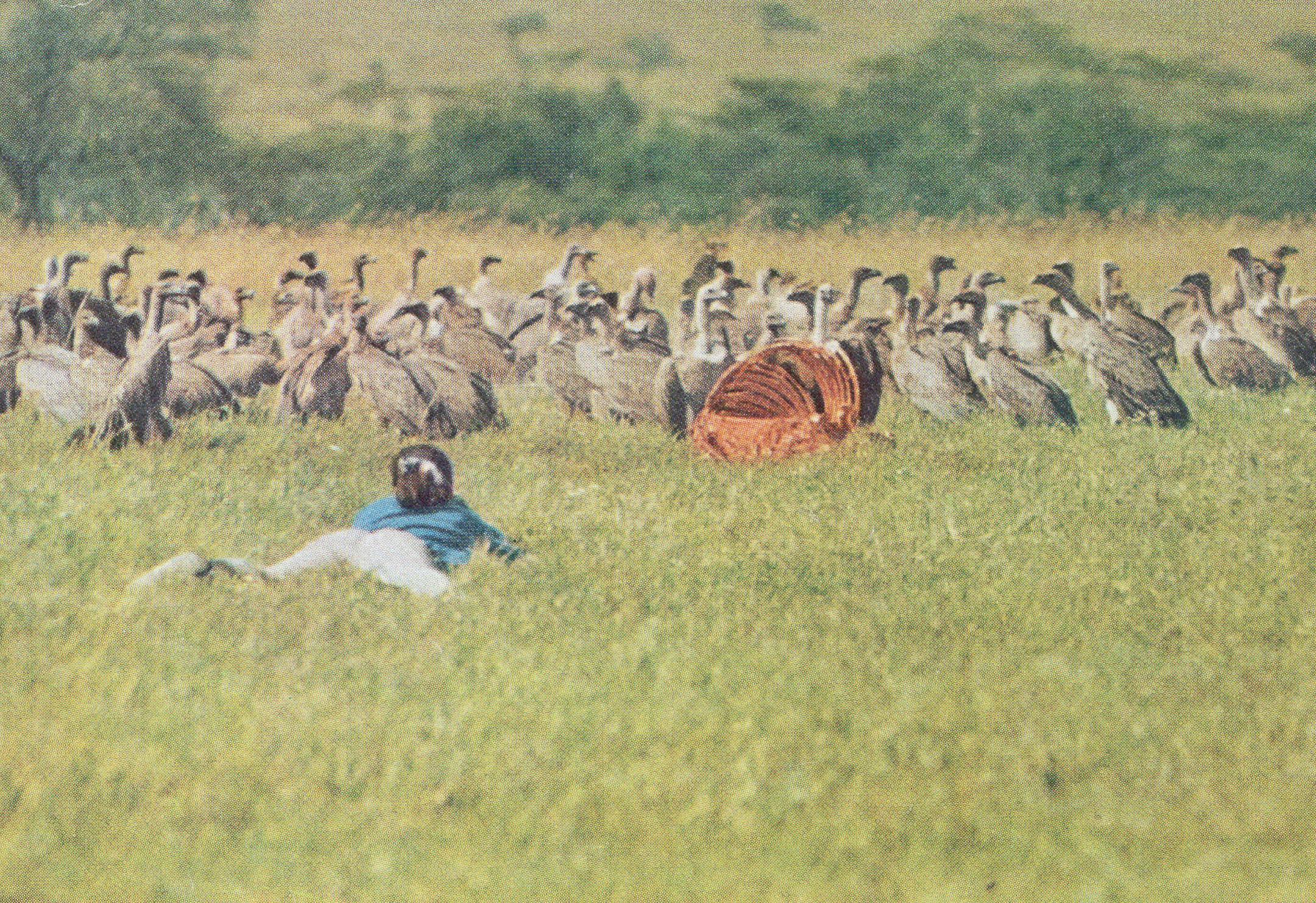

Virginia Kraft takes a mid-day hunting break in Kenya, 1957. The hut in the background was part of an abandoned village. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland

Kraft spent nearly three weeks in her element, sleeping in camps, waking before sunrise, and riding horses through the spectacular landscape, sometimes getting lost but always finding her way. “These days were some of the best I have ever known,” she wrote. Several times her group thought they were close to seeing a jaguar, but they were repeatedly stymied by thick brush, bitten by fire ants, and stung by wasps.

Finally they saw one. The scene erupted in chaos. Dogs barked. Men shouted. Kraft heard two gunshots and thought someone had killed it. But no, there it was. A spotted feline, black and gold, perfectly still, camouflaged by the speckled sunlight of the forest.

This moment in Kraft’s story gripped me with recognition of the rare kind of joy that comes when nature shows you its cards. It is a glimpse of what the world would be without people, something I had experienced just a handful of times, including once while on assignment in Peru.

Years ago, sitting in an inflatable raft on a tributary of the Amazon River, I also saw a jaguar. Like Kraft’s journey, our trip had become a survival story, filled with venomous stingrays, killer bees, vampire bats, excruciatingly itchy insect bites, dwindling food supplies, and agonizingly slow progress through a river that was not deep enough to paddle through. Then, suddenly, the majestic cat was standing shin deep in water downstream from me. It stood still and silent, not 100 feet away, seemingly relaying the message that my hardships were not the center of the tale. For a long and precious minute, it stared directly into my eyes.

Kraft must have seen this look in the cat’s eyes, too — how could she not? But after finally setting her gaze on the animal that had eluded her for nearly a decade, she raised her rifle, took aim, and shot it dead. In the SI photo spread, she proudly holds the cat’s limp carcass. A caption below boasts of its size as the seventh largest jaguar trophy on record.

Virgina Kraft shows off a jaguar after a long hunt in the jungle of Matto Grasso, Brazil, 1965. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland

Lost in the reverie of my own memory, I should have seen a violent ending. I had already learned to expect this kind of heartbreaking conclusion in Kraft’s work. But it still pained me each time. She wrote about nature with the lyricism of a poet. Her stories included rich characters and revealing quotes. They brimmed with sensory details and suspense. And, too often, they ended with the deafening crack of a gun.

After a trip to Alaskan sea ice with scientists for a 1968 story on concerns about polar bear populations, she hired a guide and killed one. On a canoe trip down the wild Serpent River through the Tehuantepec jungles in Mexico, the group slayed javelinas and tapirs. By 1970, she had taken down a tiger, an elephant, a rhino, a polar bear, an ibex, a caribou, and a moose.

She was, unapologetically, both an adventuress and a conqueress. SI senior writer William Leggett called her, in 1981, “one of the best shots that ever lived — male or female.”

THE GALS WERE GAME

“If her husband is not a fisherman, angling offers a woman even broader horizons. It is her entree to new adventures and new alliances. It is a thoroughly aboveboard excuse to get away from home and hubby as frequently as she wishes, to whip off to the islands or the interior or to one of a dozen resorts and spas where, alone, she might be viewed with suspicion, but where as an angler she is never alone. Her travels are always complete with rods, reels, boat and crew — a most respectable and businesslike combination. The fact that the captains and mates on the top sports-fishing boats are frequently young and handsome and that the husbands of women who can afford to fish such boats are more often than not old and faded though rich, is not entirely coincidental.”

Virginia Kraft

“Scourge of the Seven Seas”Sports IllustratedJuly 10, 1967

The Venice Marina is about as close as you can get to the southern tip of Louisiana, a maze of waterways and marshes that separates the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico and is ideal habitat for sea trout, flounder, snapper, marlin, and other big game. Angling is so important to the region’s economy that Venice dubs itself “The Fishing Capital of the World.”

The day before the tournament began provided a chance to hang out, warm up, and scope out where the fish might be biting. Unlike on tournament days, competitors were more relaxed about bringing along a guest. As the boat left the dock at 6:30 a.m., Weingart, the 65-year-old competitor from North Carolina who would be looking for her guide Jack the next morning, marveled that she had made it there at all. A cancer survivor, she had developed a 103°F fever and blistered lips a few days earlier. She was taking six medications and relying on the other women, now some of her best friends, to help her out. “This is where I feel most alive,” she said. “Even when I don’t feel well, I feel good out here.”

Julie Herbert, left, of Hahanville, Louisiana, fishes while captain Will Wall takes a photo of Katie Jo Davis, of Citrus Springs, Florida, on the first day of the 2023 Louisiana SLAM Tournament on June 5, 2023. Kathleen Flynn/Long Lead

In some ways, the modern version of the group echoes the IWFA’s early years, when Kraft chronicled a mix of competition and fun that defined the organization’s beginnings. Back then the women were fabulous. During the first IWFA billfish tournament in 1956 in Florida, Kraft detailed some of the atypical fishing attire worn by the event’s 66 competitors: silk pants, Chanel sweaters, gold lamé pants, a full-length mink, hairdos adorned with ribbons and lace, and hazardous footwear, although no high heels.

They were also fearless. In 10-foot waves and chilly temperatures during one tournament, competitors puked over the side of the boats. Yet soon after, the women of the IWFA were beating men at their own game, crushing world records and winning coed tournaments. They changed the sport, too, insisting that fish be thrown back alive into the sea to count for points. And they were fierce. At a competition in Cuba, the IWFA team beat Fidel Castro, who didn’t catch a single fish. “Even the most begrudging captain had to admit that, if nothing else, the gals were game,” Kraft wrote. “Before long the captains were also admitting, reluctantly or not, that there was nothing more formidable than a female who has learned how to fish.”

Kraft’s writing style hints at the way SI reflected society’s view of women in the ‘60s. It is unclear how much of that culture Kraft embodied, how much was pushed upon her by a male editorial staff, or how much of it she intentionally included to satisfy the expectations of her editors and readers. But she scoffed at the women’s unconventional attire and embedded insults throughout the story that diminished their accomplishments. “The lady may have trouble figuring out the phone bill,” she wrote in 1967, “but give her one glimpse of a leaping sailfish at 200 yards and with computer speed she will come up with a pretty accurate estimate of its length, weight and girth.”

In writing about the first big-game fishing organization created for women only, Kraft dwelled on the question of why women might want or need such a group. In her view, most of those reasons revolved around men. Women with fishing husbands cast their lines because of jealousy, curiosity, or competitiveness. Even when they won major prizes, there was no sign — at least in Kraft’s writing — that the women did it for pleasure, joy, or love for the sport.

Kraft’s writing style hints at the way SI reflected society’s view of women in the ‘60s. . . . She scoffed at the women’s unconventional attire and embedded insults throughout the story that diminished their accomplishments.

For those whose husbands didn’t fish, the sport offered opportunities to get away from home and have relatively respectable adventures without arousing suspicion about what they were up to. But as a bonus, Kraft noted, they could spend time on fishing boats with male captains. Good captains were in such demand for their ability to help even mediocre anglers win tournaments, Kraft wrote in 1963, that prospective employers sometimes bribed them with extravagant gifts: split-level homes, sports cars, even marriage proposals.

For these female anglers, Kraft made it clear that catching men was still as much of a sport as hauling in fish, and maybe even more important. Kraft ended her 1967 story not with the women or with the marine life, but with the line, “Men, we still need you!”

During my day with the women of the IWFA, I noticed something Kraft didn’t acknowledge: the strong sense of community. These women clearly adore one another. As they fished, they took breaks to drink beer, eat snacks, and pee off the side of the boat together. “When I am out on the water, it’s almost like a religious experience because I am so thankful to be able to be out there and to be with such a great group of women who love me like a sister,” Weingart told me before the trip. “They don’t expect anything out of me other than just be kind, go fishing, and have fun.” At the tournament launch party, nine of the competitors dressed up in shark costumes and performed a choreographed dance for a room full of women who whooped and cheered.

The women fish to win, but the long game goes deeper. “We come for fishing, friendship, and fun,” says Kathy Gillen, past IWFA president. “A lot of people stay members until they die.”

A photo of the 1989 Fifteenth Big Game Fishing Club adorns the wall at the Cypress Cove Big Game Fishing Club at the Venice Marina during the 2023 Louisiana SLAM Tournament kick-off party, June 4, 2023. Kathleen Flynn/Long Lead

By the end of my time at the tournament, I felt so moved by the connections I saw that I found myself reflecting on the importance of these kinds of enduring friendships in my own life. Kraft did not. She probably knew her male audience wouldn’t have wanted to read about women bonding with women, even if her editors had let it through. “Within the lush though limited captain market, trading is always brisk,” she wrote. “The rules are simple: every gal for herself — and the stakes are high.”

Nobody at the Louisiana tournament had heard of Kraft or read her stories about the IWFA before my visit, nor had they heard her views on the motivations of their predecessors. When I read this excerpt to the women while they fished, they laughed hard, especially after the part about catching men. A few female fishing guides are available now — although not many, said IFWA board member Connie O’Day. They still hear from male guides that women are better clients because they actually listen, something Kraft noted, too. All agreed that fishing with one another is different, and still preferable, to fishing with their husbands.

Caught in the middle of the exchange given the small size of the boat, Brent Ballay, the captain, smirked while the women hooted. “I’ll keep my mouth shut,” he said. “I’d rather fish with women.”

MRS. ROBERT GRIMM

“Virginia Kraft has a full personal life; privately, she is Mrs. Robert D. Grimm, wife of an advertising executive and mother of four. She is also our hunter-writer because she fills the two major requirements of the job. The first of these requirements is an obvious one. She likes to hunt. She relishes the ordeal, enjoys the laughs and appreciates the challenges of the sport.”

Letter from the PublisherSports IllustratedFebruary 22, 1965

When she returned home from reporting trips, Kraft wrote in her third-floor office of the Carmel house, which was filled with trophies from her hunting trips: the heads and skins of caribou, buffalo, polar bear, and other animals. “When other kids came to our house, they said it was like a museum of natural history,” says Aurland. “To us, that was totally natural.”

Kraft was disciplined about her work, and she depended on live-in nannies and caretakers for her kids and home. “We run a tight ship around here,” she told a newspaper reporter in 1968. “When I’m working, it’s just like normal office hours and I’m not disturbed.” At the end of the workday, she played with her kids and spent a lot of time outdoors — riding horses, skin diving, fishing, sailing, and playing tennis, which she wrote a book about (one of five she penned during her career). Not knowing what else to do with the mandatory six-month leave of absence forced on her during her pregnancies, she wrote a book during each one. She took many of her activities to extremes. A finalist in several world championship fishing tournaments, she skied competitively, raced sailboats, earned trophies for winning a national hot-air balloon race, and, according to some accounts, was inducted into the Underwater Hall of Fame for diving.

Although Kraft was often away from her kids, she took each one on adventures. Aurland remembers a month-long journey to Africa in 1972. In Ethiopia, they met Emperor Haile Selassie. When they arrived at his palace, Aurland presented him with a rifle. Then she played with the emperor’s Chihuahuas while her mother met with Selassie. After returning home, she was surprised to receive a gift of one of the dogs’ puppies — sent all the way to New York from the emperor.

For weeks, mother and daughter camped in the rainforest with their Ethiopian guides, waking at 3 a.m. to sit in a blind and wait for nyala, a spiral-horned antelope, to show up. Kraft never appeared bothered about being the only woman in these situations, Aurland says, equally comfortable in a five-star hotel or a pup tent. She espoused flexibility. “Let’s play it by ear,” was her favorite phrase. That kind of confidence got her ahead but could also be intimidating — a judgment that women who work in predominately male spaces continue to face.

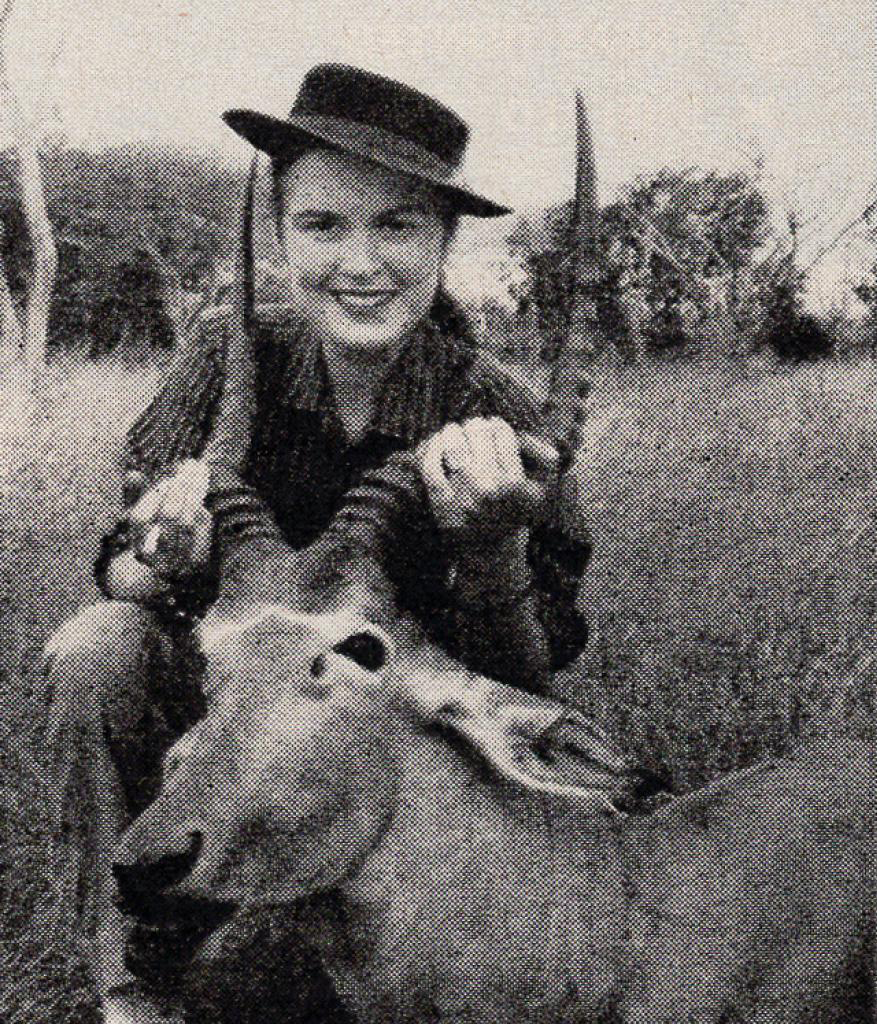

Virginia Kraft holds up the horns of a hartebeest, a type of African antelope, on an African safari, 1957. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland

Kraft did face her share of struggles as a working mother of four in the 1970s, Aurland says, especially after she and Grimm separated in 1970 and divorced the next year because of “irreconcilable differences,” according to her nephew Jon Wickers. After the split, the kids, ages 7 to 12, lived with Kraft in the house and regularly saw their dad, who lived nearby. Kraft did her best to keep things normal. She made Halloween costumes, cooked dinners, and cultivated silly traditions at home. Whenever one of their eight cats had a birthday, the pet was allowed to sit on a special stool at the table.

I wonder whether other suburban stay-at-home moms of the era judged Kraft for her commitment to work. Even if they did, she didn’t let them get in her way.

As she traveled the world and churned out stories — moving into a staff writing position at SI in 1959 and an associate editor role in 1966 — other women at Time Inc. struggled to land the same kinds of opportunities. Men were more quickly promoted from reporter to writer positions, according to MacCambridge, and women were less likely to get plum field reporting assignments. During the 1967 Masters golf tournament in Augusta, Georgia, SI sent a team of reporters that included just one woman, journalist Sarah Ballard. After a day of watching golf and conducting interviews, Ballard was also expected to cook dinner.

Nobody said women couldn’t do the work of writing, but the culture of the place implied it. André Laguerre, the magazine’s managing editor from 1960 to 1974, regularly worked until 3 a.m., then returned a few hours later at 9 or 10. He expected his staff to do the same, whether male or female, parents or childless. After-work drinking sessions were also part of the deal. “Sports Illustrated made nearly impossible demands on people’s personal lives,” MacCambridge says. “It was that kind of remorseless place that Virginia Kraft would have had to make her way in.”

Kraft did more than just make her way. She won journalism awards, gave talks, appeared on television, and garnered media attention for her successes as a woman in both hunting and writing. But from the perspective of history, Kraft stayed strangely under the radar. Despite her pioneering status, MacCambridge didn’t mention her once in his 400-plus-page book about the history of the magazine; her name didn’t come up in his research. Although he regrets the omission, he says he didn’t have anything to work with. “She was a trailblazer and an important figure, and I feel bad,” he says. “But I don’t even have an anecdote.”

“Sports Illustrated made nearly impossible demands on people’s personal lives. . . . It was that kind of remorseless place that Virginia Kraft would have had to make her way in.”

— Michael MacCambridgeKraft’s erasure from the history of sports writing may have something to do with her general absence from the offices of SI during her career there. Distancing herself from the boys-will-be-boys, hard-drinking culture based at the Time & Life Building in Rockefeller Center, Kraft lived in a world of her own. She spent about a third of each year traveling on assignment, making the outlandish claim that she covered 200,000 miles annually. And although that number is hard to believe, she was clearly prolific: In 1967 alone, she published 10 major features, including one of her stories on the IWFA. (That year she also wrote about hunting in Jordan, hunting in the Grand Canyon, fishing in Australia, and racing in a dogsled competition in Alaska.) When not in the field on assignment, she generally went to the office only a couple of times a week, staying in an apartment in the city as needed. More often, like some of the other senior writers, she wrote from home.

Kraft was something of an enigma to her colleagues. When Kirkpatrick arrived at the magazine in the mid-1960s, Kraft was already both well established and scarce in the office. On the days she did come in, she kept to her end of the hallway, less social than the writers who invited reporters to their offices or even dropped by the bullpen to chat. Kirkpatrick rarely saw Kraft, whom many called Ginny. On the handful of times he spotted or even exchanged words with her, she seemed aristocratic and classy, on another level. “I remember her having an office way down the hall at the other end, with the editors and writers and me thinking that she was like a big, big deal,” Kirkpatrick says. “I remember being very intimidated.”

He wasn’t the only one. Around the same time, Carolyn Keith started working as a summer intern at the magazine. On the only occasion she recalls interacting with Kraft, the writer emerged from her office as Keith walked by. Kraft complimented Keith’s clothing, which surprised the young intern. “At that point, she was very well known, very upper crusty,” and “she was dressed like somebody that had the money to do it properly,” Keith says. “She looked stunning.”

In fact, Kraft was so elusive at SI that every other staffer I talked with for this story who overlapped with her responded that they didn’t have anything of substance to say about her because she was either gone a lot or too important to interact with them, although she was pleasant if you managed to get a minute with her.

Beyond SI alumni, Kraft is otherwise unknown among many who do parallel work today. I talked to a number of journalists and experts on women in sports journalism for this story. None knew who she was before I told them about her.

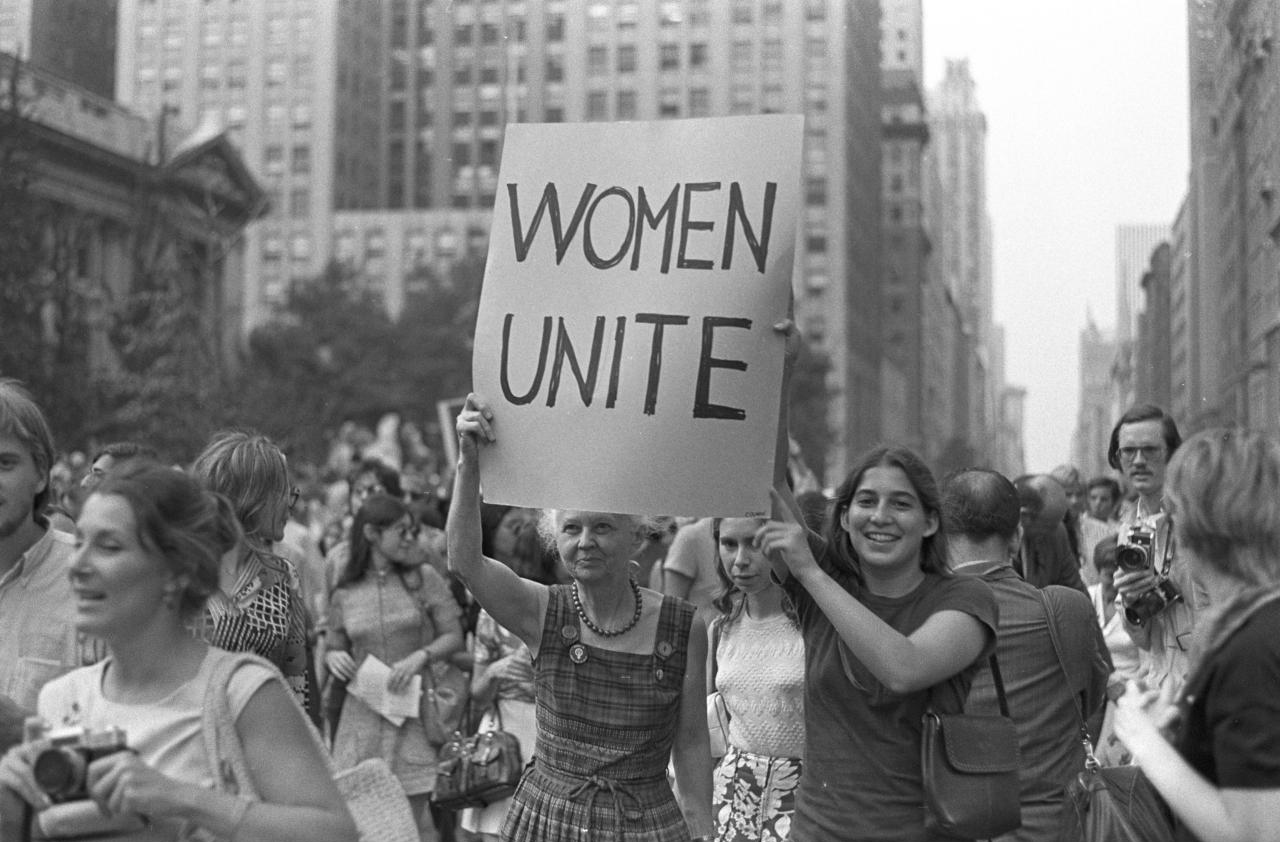

It is no surprise, then, that Kraft also appears to have been invisible when, in the spring of 1970 — a few months before an estimated 50,000 people walked down Fifth Avenue as part of the Women’s Strike for Equality March — the New York Attorney General’s office filed charges on behalf of more than 100 women at Time Inc. who complained of gender-based discrimination at Time, Life, Fortune, and SI, in violation of state law. The move followed a similar action at Newsweek, where 46 women had filed a gender discrimination suit not long before.

Although 60 women were employed at Time Inc. as researchers at the time of the lawsuit, men held all the highest-paid positions and women made only a fraction of the income. Women averaged $15,000 year to the men’s $35,000, according to journalist Ann Crittenden, who wrote a 2020 article about the conflict and its own near erasure from history. In 1970, after three years of working as a researcher at Fortune, Crittenden tried to move up to a writer position, but her male editors insisted she was too valuable as researcher. Other women felt similarly blocked from promotions. Time Inc. denied the charges. But soon after the filing, 23 women at SI signed a petition to support the cause. According to lore, Laguerre heard about the suit and asked, “Do we have 23 women at Sports Illustrated?”

The "Women’s Strike For Equality," a protest organized by the National Organization for Women, marches in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the 19th amendment, for abortion on demand, equality in the workplace, and free childcare, August 26, 1970. Bob Parent/Getty Images

At all the Time Inc. publications, men dominated leadership roles. At Time magazine, all 12 senior editors and 19 of the 20 associate editors were men. These kinds of gender disparities may have been acceptable in the Roaring ‘20s, the women of Time Inc. said in support of the lawsuit, according to news coverage at the time. But in 1970, the obstacles they faced were humiliating and illegal. There was a similar gender breakdown at SI, where the masthead from May 1970 reveals one woman editor camouflaged in a field of male counterparts: Virginia Kraft.

After the case settled in 1971, improvements came grudgingly, and then only for women who hadn’t signed the petition, according to MacCambridge. When Laguerre promoted Pat Ryan to a senior editor position that year, he offered her a raise of $3,000, which would up her salary to $21,000 a year. She insisted he match what men in the same position were making. Reluctantly, he gave her $28,000. “Every woman who fought through the glass ceiling was fiercely self-reliant,” MacCambridge says. “You had to be really willful and resilient to succeed there.”

From her perch as senior member of the staff with four children — three daughters and a son, born between 1959 and 1964 — Kraft left no evidence of any involvement in the lawsuit and no public comments about it. Maybe she was in Carmel with her kids. After all, family was very important to her, says Adrienne White, 94, a college classmate and longtime friend of Kraft’s. Perhaps she faced financial stress as a divorced mother with a full house of young children. Or maybe she was away on reporting trips when other women were fighting to catch a break.

Time Inc. denied the charges. But soon after the filing, 23 women at SI signed a petition to support the cause. According to lore, Laguerre heard about the suit and asked, “Do we have 23 women at Sports Illustrated ?”

Still, her apparent absence from the struggle is notable. I found it unsettling. She had been doing men’s work for well over a decade, and she had the potential to influence a generation of women behind her. Instead, it seems, she made a deliberate decision in 1970 to pursue her own interests rather than fighting for other women. “I don’t remember her saying, ‘Listen girls, let’s have lunch together and talk about it,’” Keith says. “She was not part of the daily or weekly scene.”

There is another possibility. Maybe Kraft saw that choice as a different way of fighting the fight. Her contribution to women’s lib, she told a reporter in 1972, was that she “wanted to cover hunting and fishing and the editors had no objections.” She didn’t consider herself a feminist, Aurland says, so much as motivated to do what the men were doing. She was an individualist, Wickers adds: industrious, independent, and always busy.

Whatever she thought about the lawsuit and women’s struggle, Kraft had, it seems, fully embraced her role as a huntress, tending to her own pack while stalking her ambitions. This contrast, more than anything else, may have set her up to be overlooked. To make it at SI as a woman in a field of men, she’d had to become a kind of apex predator, determined and willing to take what she wanted. But leaning in to an ambitious male persona actually made her harder to recognize as a role model later, especially through a contemporary lens in a world where so much wildlife is now at risk and women are supposed to have power independent of men.

Kraft’s views on nature, in particular, have since proved controversial. In the pages of SI in 1963, she criticized Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, citing sources who argued that pesticides were good for wildlife. To this day, multiple books point out her critical take of Carson, while her role as a woman journalist remains largely unmentioned. Her passion for hunting wasn’t always popular, either; today the beat no longer has a place in major sports publications. She could have been remembered forever as a trailblazer. Instead, the very thing she needed to do to be a pioneer — hunting — may be what prevented her from gaining that recognition.

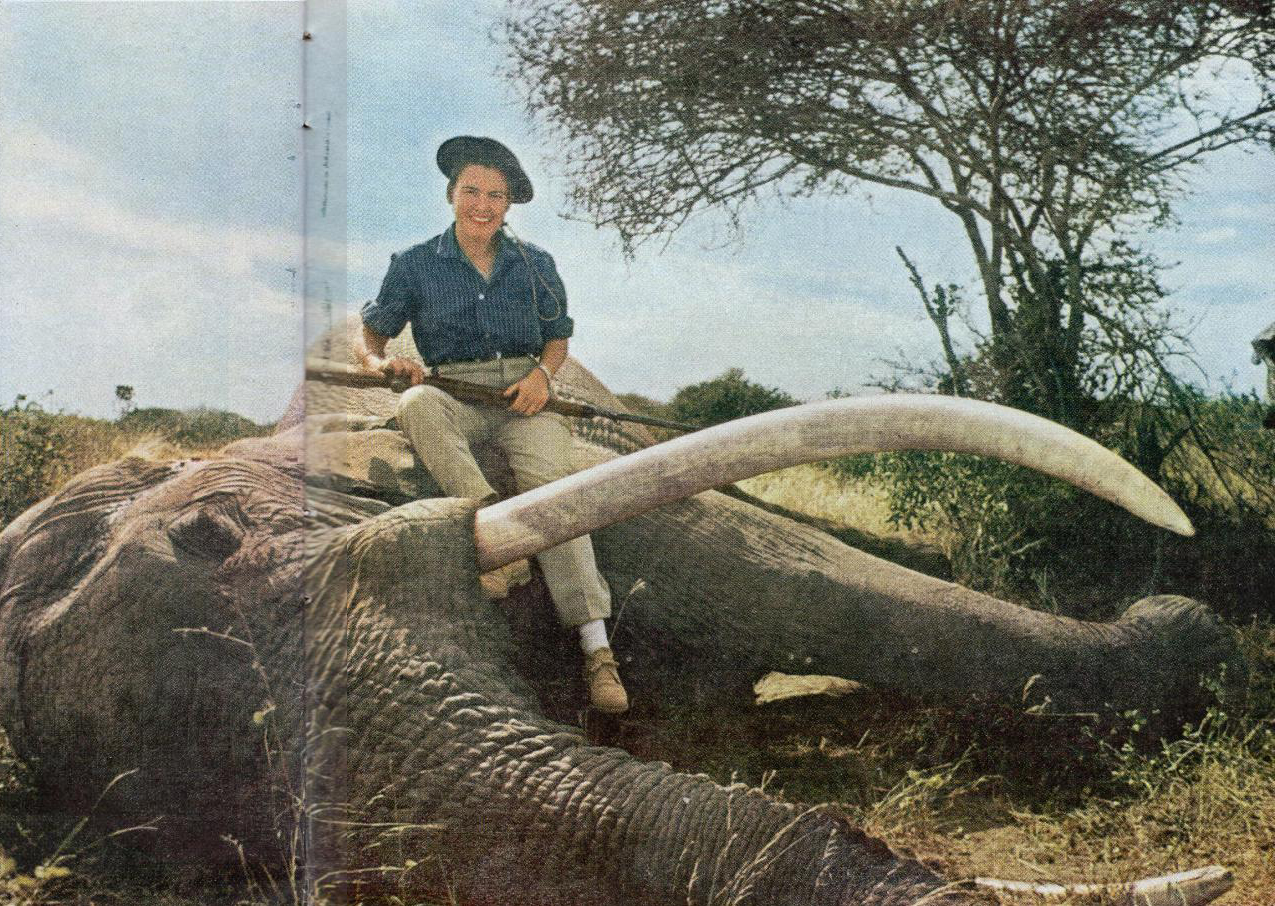

Virginia Kraft sits atop an African elephant, minutes after shooting it with a Winchester .458, in Kenya, 1957. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland

Even at the peak of her journalistic success, Kraft felt like many people didn’t understand her. She appeared on The David Frost Show in 1971, described only as a “big game huntress” rather than a writer or even an angler. In the interview, Frost ambushed Kraft. “He told her would ask about stories but attacked her,” Aurland says.

Still, with her persona well established by then, Kraft did not back down in the interview. Wickers, who was 5 or 6 years old when it aired, watched it on a black-and-white TV. “She kept her composure perfectly, and she explained that if everything’s utilized and recycled properly, it’s the healthiest way, it’s the way of nature,” he says. “She boxed her way out of a corner, and it was extremely, extremely impressive. I never forgot it.”

In her mind, Kraft was an animal lover, no matter how many creatures she killed. The family had many pets: horses, cats, dogs. Wickers, who lived with Kraft and her children for a summer when he was 16, once watched her, nearly in tears, carefully pull a rodent out of the mouth of one of the cats. Another time she scolded a hunter for improperly taking down a game animal, causing it to suffer. In multiple stories, she reported on conservation efforts that fought for kangaroos, white rhinos, the Arabian oryx, white crowned pigeons, and others.

“Big game hunters are often misunderstood,” she told The Tennessee Sun in 1970. Illegal poaching was the problem, not licensed hunters. Hunters, she said, “don’t simply destroy animals, but they replace them and are deeply concerned with ecology.”

I found myself facing a paradox in both the life of Virginia Kraft and the way I thought of her. Just as she simultaneously adored animals and killed them, I both detest the idea of hunting and admit she had a point. Like Kraft, I have written about counterintuitive environmental efforts that sacrifice living things for the sake of a bigger picture. I have covered conservation projects that kill invasive animals to save native ones. And I have documented the way that hunting groups, in order to preserve the animals they want to shoot down, have allocated billions of dollars to protect vast habitats. Those efforts have, among other benefits, allowed wetland fowl to thrive amid global declines of other kinds of birds. Although some of Kraft’s views seem misguided now, someday mine may, too.

Kraft may have continued killing animals and pursuing her dreams while other women vocally fought the patriarchy. But in her life and through her words, I started to see something more subtle, and possibly more subversive. Given the obstacles that stood between her and success in the context of her time, she was willing to stand behind her belief that two opposing concepts could coexist. The courage required for her to do that highlights how far we’ve come over the past 50 years.

UNEQUAL OPPORTUNITIES

“DuBois’ answer arrived the next day: ‘Women don’t sled-dog-race with men for much the same reason they don’t play football with them — too rough.’ But he was enthusiastic, anyway, about the idea of my entering and he soon managed to arrange for a team of dogs. . . . Busy in New York on other assignments, I undertook to prepare myself physically by lifting weights, doing sit-ups and knee bends, running along crowded sidewalks past startled doormen, riding stationary bicycles and not-so-stationary horses and by jogging several times a day up and down the 16 flights of stairs to my apartment. On the day I was to leave for Alaska, I was a regular female Jack Armstrong.”

Virginia Kraft

“Belle of the Mushers”Sports IllustratedJanuary 23, 1967

With an insatiable appetite for adventure and new experiences, Kraft made it clear through her actions that women could do anything men did. With that approach, she laid out a kind of playbook for how to follow in her footsteps: Act without hesitation and display only confidence. Equity, her stories seem to say, was there for the taking.

But Kraft was not the beginning of the end of gender imbalances in sports, outdoor, and adventure journalism — far from it. Although women now outnumber men in journalism schools and programs in the U.S., sports journalism remains stubbornly male. According to data from more than 100 websites and newspapers compiled by Richard Lapchick, director of the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at the University of Central Florida, in 2021, fewer than 15% of sports reporters were female, up from 10% in 2006. Just under 17% of sports editors were female, compared with 5% in 2006. Nearly 70 years after Kraft joined SI in 1954, men continue to dominate the most important jobs: editors, columnists, executive management positions, long-form feature writers. The situation is even worse for people of color, particularly women. The survey didn’t mention nonbinary or trans people.

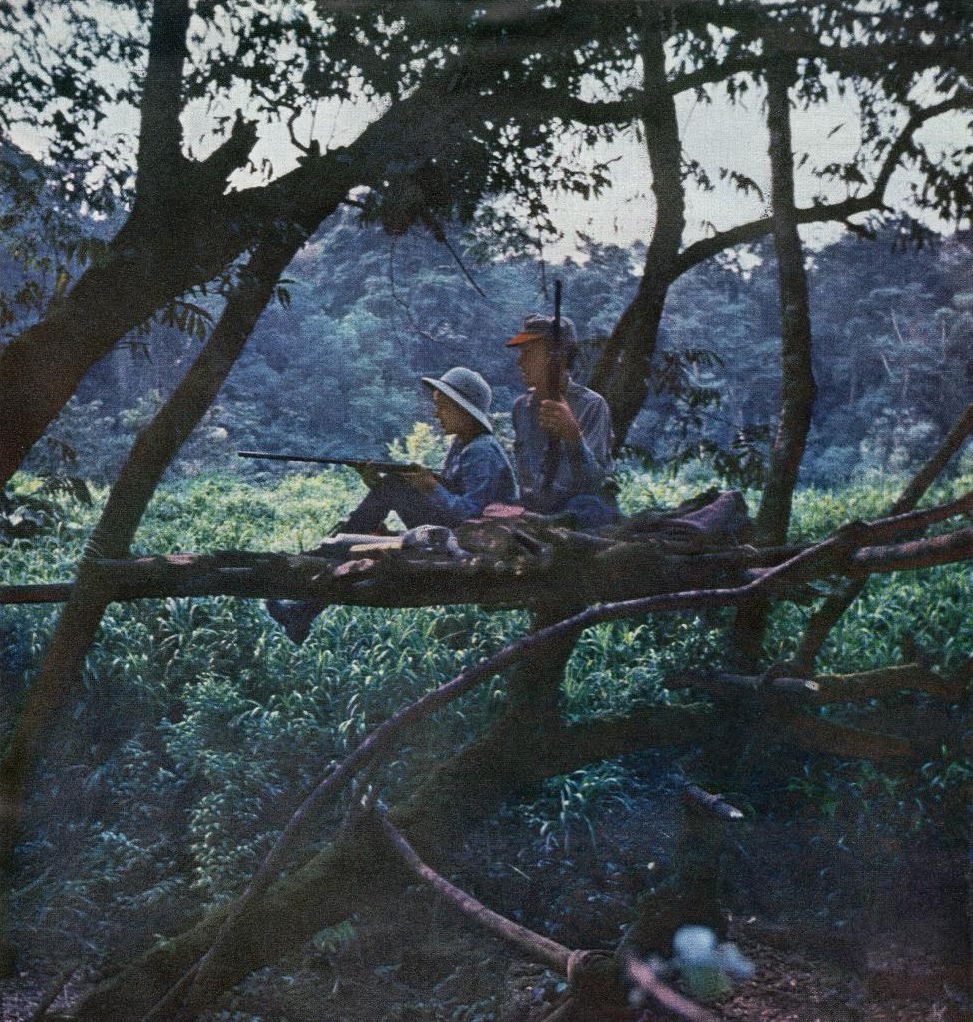

Virginia Kraft and Robert Grimm hunt jaguars from a tree in southern Mexico, 1959. Photo by Walt Wiggins via Kim Wiggins

When Vicki Michaelis, director of the Carmical Sports Media Institute at the University of Georgia in Athens, started covering high school sports for The Palm Beach Post right out of college in the early 1990s, coaches called her “honey” and offered to explain the sports to her. Still, given the pivotal gains women had made in the previous decades, Michaelis was sure things were heading in the right direction.

Some of the first equitable inroads into sport journalism came in the 1940s, when sportswriter Mary Garber broke into the male-dominated newsroom and paved the way for Kraft. Then in 1978, SI writer Melissa Ludtke earned women reporters access to locker rooms by prevailing in a lawsuit against Major League Baseball. In 1981, Christine Brennan became the first woman sports reporter at the Miami Herald; in 1988, she was named the first president of the Association for Women in Sports Media. Soon after women took on more roles in the industry, covering big-time sports. “If you would have asked young me in the 1990s if [the work] would be done by 2023, I’d be like, ‘For sure,’” Michaelis says. “There were other women, and we were young, so we were like, ‘Man, think about what we can do in the next 20 to 30 years — this is all going to be solved!’”

But an uptick in major opportunities for women in sports journalism has occurred only recently. It wasn’t until 2017 that Outside magazine, one of today’s top adventure publications, announced efforts to improve diversity in who it covered and who did the writing. The next year, Latria Graham wrote a story for the magazine debunking stereotypes about Black people in the outdoors. I started reporting my first Outside feature story — about a female psychologist for a female editor — the year after that.

In a post-MeToo world it’s hard to explain, even to myself, how I could have not consciously recognized that my gender might have been one of the reasons it took me 20 years to achieve one of my career goals, even as I saw younger male writers breaking in. And I’m not the only female journalist who feels this way.

With an insatiable appetite for adventure and new experiences, Kraft made it clear through her actions that women could do anything men did. With that approach, she laid out a kind of playbook for how to follow in her footsteps.

In 2018, Kim Cross wrote a series of articles for the Outside about equity in sports. As an athlete and journalist, Cross has long been familiar with being one of the only Asian-American women she knew doing everything she has done: competitive waterskiing, mountain bike coaching, award-winning sports journalism, and more.

Recently Cross started reflecting on the complicated ways that gender has played out in her career. In both sports and writing, she has noticed that women become less collaborative as they reach higher levels, where there are fewer spots for them. Women, and especially women of color, she says, have to work harder and be better to reach the same positions and achieve the same pay levels as men. “I honestly didn’t feel like being a woman was a disadvantage until the last few years, when I started thinking, ‘Oh, yeah, sometimes women are kind of treated like Junior Varsity in the sports writing world,’” Cross says. “Maybe I was just really naive.”

In accepting the way things were because there didn’t appear to be another choice, how we thought — or didn’t think — may have been similar to how Kraft viewed her world. By the time the women at Time Inc. filed their 1970 lawsuit, Kraft may have already realized that she was going to advance in the very male world surrounding her only if she beat the men at their own game and became one of the best shots who ever lived. Maybe she had come to see herself as something different from the women who came after her. They were taking collective action, but she’d had to do it on her own. It’s hard to be a role model, after all, when you’re busy doing the hard work of being first.

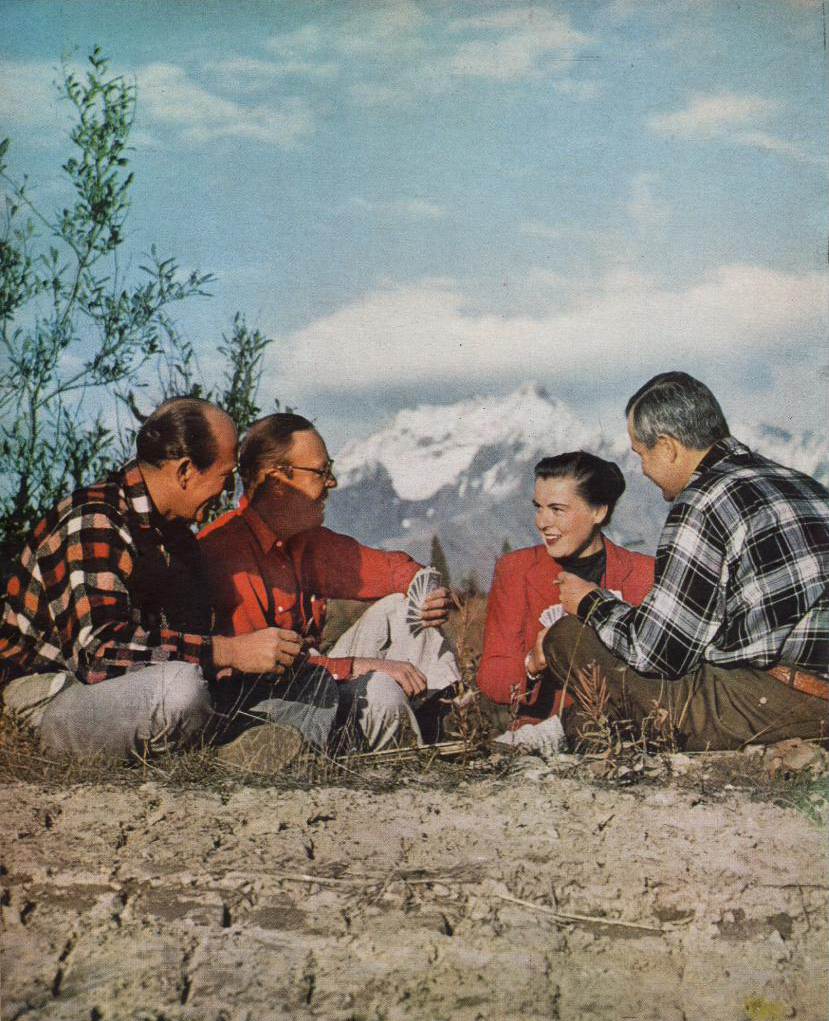

After a hunt, Alaska adventurers Lieut. Cononel Lew Wright, William D. Vogel, Virginia Kraft, and Michael Finnel relax and play cards. Courtesy Virginia Kraft Payson Estate

It’s hard to be a role model, after all, when you’re busy doing the hard work of being first.

Even if Kraft didn’t act the part of a new wave feminist, marching in protest parades or signing petitions, it’s possible her byline filled that role for an unknown number of women who read SI early on, giving them a chance to see themselves reflected in its pages. “Let’s say you’re a young girl reading Sports Illustrated in the ‘60s and you see Virginia as a name and a byline,” says Michaelis. “That’s incredibly powerful if that’s something that you think you want to do.”

All the currently working women journalists I spoke with said they wished they’d known of Virginia Kraft before now. Given the challenges I encountered while excavating her life in search of a hero, this sentiment struck me. Back when I’d channeled Kraft to get invited to the fishing tournament, I had wanted to see myself in her — and in many ways I did. Even as I found differences between her life and mine, I came to identify with her, including the parts I had initially viewed as shortcomings. Working, traveling, and raising kids already makes it hard to find time for anything else. I can only imagine how much harder life would be if chasing your ambitions also required ignoring society’s rules. Put in the same position at the same time, I wonder how many women journalists of my generation would have turned down the opportunities Kraft seized. Or, unlike her, would we have been too timid or uncertain to seize what we wanted?

But Kraft never quit, and in that trait alone I found inspiration. Revisiting her literary legacy prompted me to think about my own career and what I want to leave behind, given the different set of circumstances I started with. I kept thinking about the day she walked into the offices of Field & Stream for the very first time, saw only men, and talked her way into a job anyway. Kraft did so without role models, but I have always seen women writing and women in leadership roles. She spent hours immersed in old magazines, teaching herself the language. I received mentorship from more experienced writers. Kraft may not have deliberately shown other women journalists the way forward, but with the trail women before me blazed — and an understanding of Kraft’s lonesome climb — I’m now motivated to make that journey easier for the next generation of women journalists.

Hunter and Prey

“For a man who owns a spread on the coast of Maine, a horse farm in Kentucky, a 100-acre estate on Long Island, a house at Saratoga, an apartment on Fifth Avenue and a Hobe Sound mansion on Florida’s Gold Coast, deciding on any given day where to rest his head could be perplexing. But for Charles Shipman Payson, the owner of all of the above as well as a yacht and a plane, the decision is simple.”

Virginia Kraft

“At Payson’s Place, He’s Just Plain Charlie”Sports IllustratedApril 18, 1977

More than two decades after she started working at SI, Kraft traveled to South Central Florida to hunt with Charles Shipman Payson, the owner of the New York Mets, who was then in his late 70s. She had interviewed him before, but this time was different. Aurland was 17 years old and, as she remembers it, got a call from her mother while she was on that reporting trip. “You won’t believe what happened,” Kraft confided in her oldest daughter. “We were out in the buggy, and he suddenly turned to me and kissed me.”

“I always could see something like that coming, and I knew how to fend it off without causing bad feelings,” Kraft told Newsday in 1987. “But with this man, my guard was down. I mean he was seventy-eight years old, he had already been married to a woman for fifty years, he was old. I didn’t see him as a man. He was simply a story.”

Charles Payson poses for a portrait with his rifle in hand, for a 1961 feature in Sports Illustrated written by Virginia Kraft. She would profile him again in 1977, and marry him the same year. Marvin E. Newman/Sports Illustrated

Kraft was 47, by then an associate editor at the magazine. Payson’s health, according to some sources, was ailing, and he had four grown children from his previous marriage to Joan Whitney Payson, the extremely wealthy original owner of the Mets, art collector, and horse breeder. Payson’s children were older than Kraft was. It seemed crazy.

The kiss, which was neither friendly nor fatherly, threw her for a loop. Payson was persistent, throwing one of Kraft’s trademark traits back at her. “I said, ‘Mom, you know what? If you like him, it’s not crazy,’” says Aurland.

Kraft’s feature about Payson ran in SI in April 1977. In December that year, the two were married at the Episcopal Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Falmouth Foreside, Maine, with around 54 guests in attendance, mostly family. Virginia Kraft became Virginia Kraft Payson.

Her new husband’s children were not enthusiastic about the May-December match, complaining openly that Kraft was in it only for the money. After Payson died in 1985, they sued her for fraud, claiming she had tricked him into rewriting his will at least 16 times in the seven years they were together. The final version left most of his liquid wealth to her, including an $18 million estate and the interest on a $30 million trust fund to be split among the children after her death. To them, he bequeathed only a collection of art — albeit expensive art. Kraft argued that their love was real, that his children didn’t know her, and that she was a fighter who did whatever it took to preserve his reputation and achieve her own vindication.

She won, like she usually did, although sour feelings persisted, bubbling over in 1987 news coverage of the $53.9 million dollar sale of the Van Gogh painting “Irises,” which the Payson family owned. At the time, it was an art auction record. One of Payson’s daughters reportedly told Forbes that Kraft was “a big-game hunter and my father was the prey.” (Payson’s one surviving child from his first marriage to Joan Whitney declined to be interviewed for this story.) A quarter of the sale price went to charity, and the rest was put in a trust for Payson’s children.

Soon after her marriage to Payson, Kraft left SI and said goodbye to journalism. Her last story for the magazine, on December 11, 1978, was about the invention of a machine to match tennis players with rackets — an oddly mundane service piece to finish on after more than two decades of writing wild feature stories. The couple bought a thoroughbred horse in Kentucky on a whim and a winter training facility in Florida. For a time, they owned the house on Long Island that some believe inspired the mansion F. Scott Fitzgerald described in The Great Gatsby. Like everything else she did, Kraft dove completely into the horse business and worked twice as hard as anyone else. “When she decided to do something,” Aurland says, “she went all the way.”

One of Payson’s daughters reportedly told Forbes that Kraft was “a big-game hunter and my father was the prey.”

Owners Charles and Virginia Kraft Payson with their horse Carr de Naskra during "The Fountain of Youth Stakes" at Gulfstream Park, March 18, 1984. Jacqueline Duvoisin/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images

The marriage and the horses appear to mark the end of Kraft’s major hunting expeditions. She was too busy learning the ropes of her new obsession. Besides, the pursuit of big game had served its purpose and given her a career as a journalist — a career she didn’t need anymore, just like she no longer needed to preserve her original last name for the purpose of a byline. With her departure from the field just a few years before the next generation of women entered sports writing, her impact faded into the magazine’s archives.

In the meantime, she turned her full attention toward horses. And just as her immersion into journalism had led rapidly to adventure and achievement, success in horses came quickly, ultimately bringing in a lot more money than journalism. Dozens of the farm’s horses placed well in major races, and Kraft continued breeding and racing horses after Payson’s death. One stallion, St. Jovite, was named the European Horse of the Year in 1992 and later sired eight winning horses that went on to earn more than $7.5 million.

Kraft continued to gain accolades and honors, earning Breeder of the Year from the Thoroughbred Owners and Breeders Association in 1997. In her later years, she appeared in an ad for a private jet business. She married twice more, first to thoroughbred owner Jesse M. Henley, Jr., and after he died, David Libby Cole, a real estate broker. Her life, she often said, was a “magic carpet ride.” Kraft died from complications of Parkinson’s disease in January 2023 at age 92.

Only after Kraft transitioned out of the media and into horses did profiles written about her start to probe on her journalistic impact beyond the big animals she killed or the beauty products she carried on safari. That’s when she, too, finally appeared willing to reflect on what she had done. In both her careers, she told Siena College graduates, it took “long hours and determination to try and do everything just a little bit better and sometimes a little bit differently than it had been done before.” In 2015, she said SI took her in because of her background in the outdoors, but her position was not secure, especially in the beginning. “Every guy who was hired looked around and figured, ‘I can knock her off first,’” Kraft said. “I just did my job and created the opportunities.”

“With the magazine, you did all this research and wrote a story, but a week later, aside from Mom and the scrapbook, it was old, outdated. With horses, you do the research, and then the result is part of your life. You live with it for years.”

— Virginia KraftFriends and family described Kraft as loyal, generous, energetic, and fun. But even with the people she loved, she didn’t want to hear about your aching back, says Diana Kaylor, 83, who had been friends with Kraft since 1989. “She was not somebody who lived with delusions,” Kaylor says. She didn’t brag about accomplishments. She preferred to blaze her own trail instead of waiting to be shown the way or making a big deal out of what she had done.

By the time the SI era was behind her, Kraft acknowledged that she had developed some skills she treasured and that there were some downsides to journalism, including its transience. In 1992 she told an equine magazine that the horse business was like journalism, only more enduring. As a journalist, she had been criticized for over-researching, she said. But that tendency to dive deep into her interests paid off in horse breeding. “With the magazine, you did all this research and wrote a story, but a week later, aside from Mom and the scrapbook, it was old, outdated,” she said. “With horses, you do the research, and then the result is part of your life. You live with it for years.”

A NEW KIND OF REVOLUTION

“I tried my hand at it, too, and I was surprised. In three days of continuous fishing I lost six sails on 10-pound line before bringing my first alongside. All six might have been caught by an experienced angler, and with each mistake my respect increased for the women fishing the tournament. When finally the seventh sail was officially caught and released, I was soaking wet, there was a foot of water in the cockpit, a callus across my left palm and an ounce of salt water in the works of my watch. But the important fact was that I had whipped this fish, not by luck or strength but by careful manipulation of a wisp of monofilament.”

Virginia Kraft

“The Ladies and the Sailfish”Sports IllustratedFebruary 1, 1960

Rising before dawn on the first morning of the IWFA tournament, I wondered if Kraft had trouble sleeping on reporting trips, like I sometimes did. And after drinking coffee to sharpen my senses for the reporting hunt ahead, I marveled at the chasm created by history over the decades since she first started writing, alone, and these women arrived to go fishing together. At 6 a.m., boats started zooming away from the docks, scattering across the delta past oil rigs and squawking gulls, each guide motoring off to secret spots for eight hours of fighting fish.

Waters were calm through the morning, with some rain dousing competitors in the early afternoon. By 3 p.m. the participants were back on the dock in Venice, Louisiana, where they handed in their score sheets for tallying. Weingart, the cancer survivor from North Carolina, won an award for making the competition’s first catch, recovering from her early struggles to find her guide. Prizes also went to daily wins, top teams, and other achievements like reeling in the fish with the most spots. Connie O’Day, a longtime member in her 70s who organized the shark-dancing performance, won the whole thing, taking home a coveted gold disc. Over the three-day event, the IWFA anglers caught nearly 1,600 fish, a record.

Kathy Gillen, left, of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Brenda Moore, of Austin, Texas, and Connie O’Day, of Pearland, Texas, fish off the coast of southeast Louisiana the day before the 2023 Louisiana SLAM Tournament begins on June 4, 2023. Kathleen Flynn/Long Lead

When Kraft wrote about the women of the IWFA in 1967, her words spooled out under an ominous headline: “Scourge of the Seven Seas.” And although SI’s first female adventure writer might have marveled at how joyful — and uninterested in seducing their fishing guides — the group’s members are today, she would have been unsurprised by their impressive haul. “By the time the IWFA was 5 years old, 23 of its members accounted for 27 of the world-record catches,” she wrote then, lauding them for their win over Castro in Cuba. “The IWFA victory was, as one Havana daily put it, ‘a new kind of revolution.’”

Perhaps the wildest thing about Kraft’s wild tale is that, despite her remarkable ability to shape-shift — mimicking male writing, staying downwind from mountain goats, dressing the part of a blue-blooded Manhattanite — she didn’t promote herself or her achievements as revolutionary. Yet she blazed a new path, leaving in her wake both accomplishments and casualties, building a life that was unimaginable for just about any other woman at the time. Virginia Kraft hunted and fished alone. In later generations, we don’t have to.

The women of the IWFA stick together and wouldn’t have it any other way. When I joined them, O’Day — who helps run the organization’s junior angling program — handed me a fishing rod baited with frozen squid. Just as Kraft did in her 1960 story, I gave it my best shot. First I dropped the hook to the bottom and almost immediately felt a tug. But when I started to reel in, it was too late. The squid was gone and so was the fish. The same thing happened on my second try. The third time, I started cranking the reel more quickly and soon was locked in a tug-of-war with the fish.

Virginia Kraft hunted and fished alone. In later generations, we don’t have to.

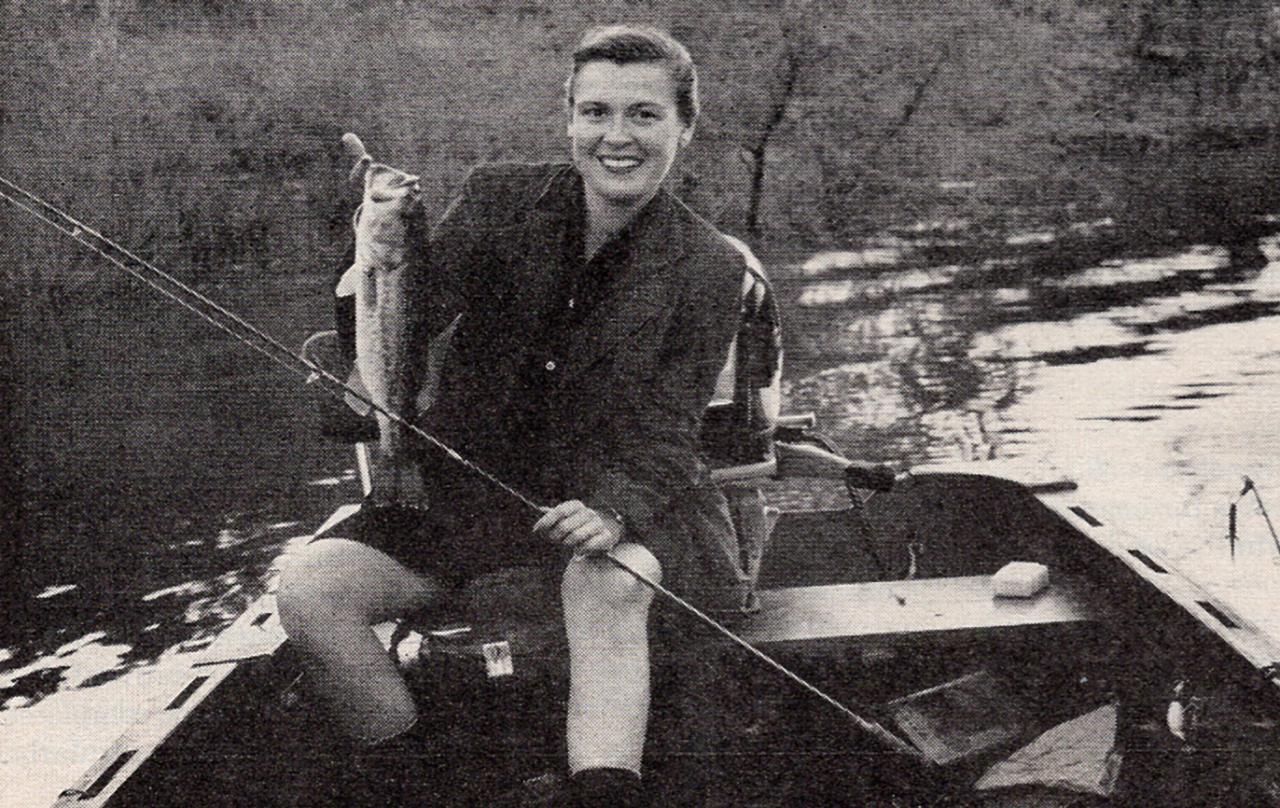

Virginia Kraft displays a 2.5 lb. bass caught in Center Hill Lake in the Tennessee Valley, 1958. Photo by Robert Dean Grimm via Tana Aurland